Rerun: Concrete Cowboy and Other Black Westerns

Movies to pair with Netflix’s rare offering.

4/3/2024: I can't stop listening to Beyoncé's Cowboy Carter. We are only a few months into 2024, but I will be surprised if it's not my favorite album of the year. If it's not, it will have been a very good year.

A few days ago, I published my review - music reviews are rare for both myself and this site. One thing I couldn't really squeeze in, however, was the album's connections to black western cinema. Aside from a reference to The Hateful Eight, I couldn't find space to talk about The Harder They Fall (I film I really enjoyed) or Five Fingers For Marseilles (I film I have yet to see) and how they inspired Beyoncé. This was particularly frustrating for me because, at the end of the day, this is a website largely dedicated to movies.

What it did get me thinking about, however, is this piece I wrote a few years ago around the release of Concrete Cowboy, a film I liked at the time and one that Netflix seems to make less and less. In one of the earliest pieces on the site, I write about other black westerns and milestones throughout the genre. It's not quite the kind of thing that would become my B-Sides series, but it doesn't feature heavy hitters like Buck and the Preacher either. It's got a little bit of everything, which I was I liked it. And why, along with my continued raving of Cowboy Carter, I decided to rerun it today.

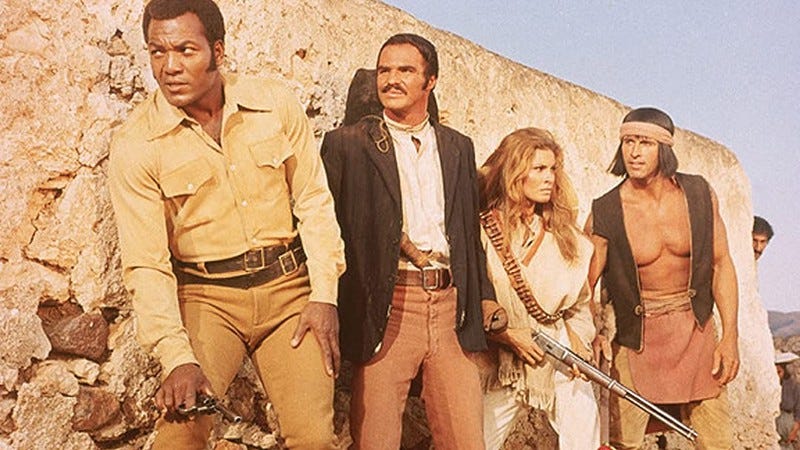

100 Rifles (1969)

When half-breed Indian Yaqui Joe robs an Arizona bank, he is pursued by dogged lawman Lyedecker. Fleeing to Mexico, Joe is imprisoned by General Verdugo, who is waging a war against the Yaqui Indians. When Lyedecker attempts to intervene, he is thrown into prison as well. Working together, the two escape and take refuge in the hills, where Lyedecker meets beautiful Yaqui freedom fighter Sarita and begins to question his allegiances.

The racial makeup of this film is very messy. I mean that in both the figurative sense and the literal — sometimes the makeup for the black and brown face is splotchy. Yes, the film features black cinema icon Jim Brown as an American lawman and aside from a few obligatory remarks, little is made about his race. He is allowed to be strong, smart, and persuasive. However, he is only one third of the trio that consists of Burt Reynolds (who, in real life, lied about having Cherokee ancestral roots) as a half Native Mexican-half white bank robber with a longer-than-normal mustache to counteract his white skin, and half white-half Bolivian Raquel Welch as a Mexican Indian.

They share the screen with a lot of actors in racial makeup.

The movie does, however, deal with other racial aspects of the film with success. The movie features the first interracial sex scene in film, just two years after Loving v. Virginia highlighted the growing number of interracial relationships in the United States.

The movie also has a surprisingly decent message regarding racial differences. Despite the fact that many characters in the film disregard each other or their motives based on the color of their skin, they put it all aside in the finale to fight for the common good. There is an unspoken understanding that black vs. white vs. brown is not the same thing as good vs. evil.

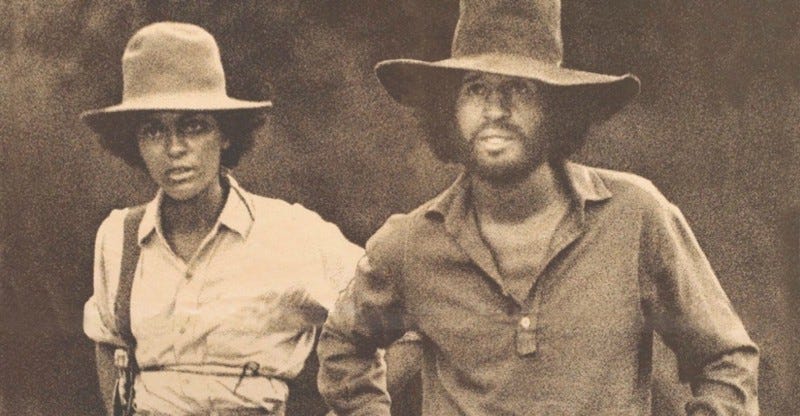

Thomasine and Bushrod (1974)

A pair of thieves operate in the American South between 1911 and 1915, stealing from rich, white capitalists, and giving to Mexicans, Native Americans and poor whites.

The following contains spoilers.

Thomasine and Bushrod — always in that order. She’s also always on the left of every picture. She’s the left brain — serious, calculating, methodical. He’s the right brain — overly generous, free form, impulsive.

Before Thomasine and Bushrod begin their crime spree, they share a moment splashing around in the river. They plan their future with lots of land, kids to raise, horses to tend to. They make this promise to each other while the calming title song sings nothing but their melodious monikers: Thomasine and Bushrod.

As soon as they begin robbing banks, that idealism fades. She worries that he isn’t committed because he gives so much of their money away to others in unfortunate positions. He figures himself a modern day Robin Hood, taking back what the comfortable whites stole through systemic infringement. Quickly, their turbulent history together rubs up against their rose-colored future.

On top of that, it’s a “lovers on the run” movie, so you can guess how it ends. But as the credits roll, they flashback to that scene splashing around and laughing in the river. The full lyrics to the song are revealed and we revel in their spirit, even if just for a moment, even if we know the truth:

Thomasine and Bushrod

Were more than just two names

But why and what they wanted

Is not hard to explain

Now if you want to judge them

I’d like to know your name

When Thomasine and Bushrod

Were riding on the plain

They had a love love love love love

But it was so very strange

With money, love, and happiness

They couldn’t be ashamed

They had a love love love love love

But it was more than a game

Once Thomasine and Bushrod

Just turned that into pain

Thomasine and Bushrod

Went looking for a home

Two guns in between ‘em

They really weren’t alone

They grew so big a legend

Some thought they couldn’t die

But for Thomasine and Bushrod

Who could only ask the sky

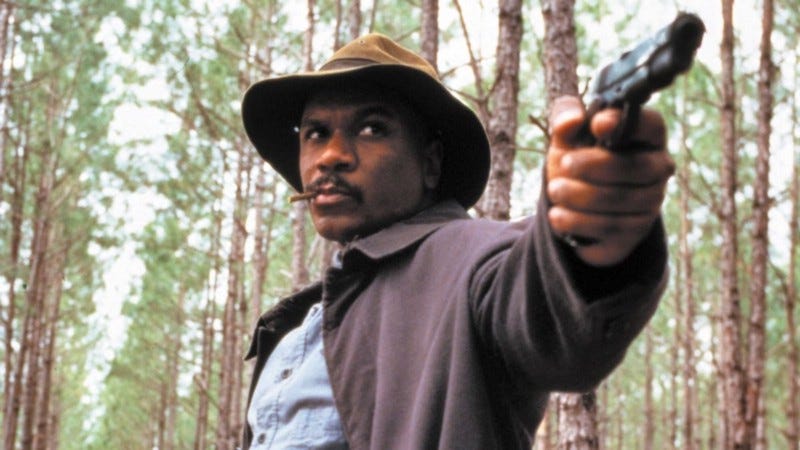

Rosewood (1997)

Spurred by a white woman’s lie, vigilantes destroy a black Florida town and slay inhabitants in 1923.

As the 100th anniversary of this true story has come and gone, this movie can show us just how little as changed over time. Progress has been made, eyes have been opened, injustices brought to light, but some things have remained exactly the same: mob mentality, passive racism, white fragility and more all come to mind.

Characterizing this is as a western seems disingenuous at first, but it’s a label that really works here, (especially if we’re okay with labeling something like Nomadland as a western.) A lone man in black strolls into a small town to start a quiet life — and finds anything but. Makeshift bounty hunters and imitation lawmen carry out their own version of justice in a lawless place, blurring prejudice, moral obligation, honesty, and remorse into an ending only Singleton (and few others) can handle with such skill.

Django Unchained (2012)

With the help of a German bounty hunter, a freed slave sets out to rescue his wife from a brutal Mississippi plantation owner.

This film has been shrouded in controversy since its release almost ten years ago. The n-word is uttered an exorbitant 110 times in 165 minutes. Grotesque depictions of slavery seesaw grotesque scenes of violence. And Tarantino’s revisionist view of history has been controversial since he first tried it. In that regard, one of my favorite filmmakers, Spike Lee, refused to even see the film, saying, “American slavery was not a Sergio Leone Spaghetti Western. It was a Holocaust. My ancestors are slaves stolen from Africa.”

With all this being said, however, few aren’t aware of what they are getting themselves into when they press play on a Tarantino opus.

Many argue that Tarantino’s signature use of violence and vulgarity gives the film a pastiche that could cause it to be overlooked otherwise.

What does it mean to be free in a world that doesn’t respect that freedom? How often do white people assume the atrocities of racism because they believe it’s too bothersome to be an ally? When do we respect the law and when do we sidestep it for the sake of our moral clarity?

This film begins in 1858 and every single one of those dilemmas are debated on Twitter, 24 hours “news” (opinion) shows, and the halls of Congress every day.

If you can take the Tarantino-isms for the lampoon many hope them to be, you can find those themes throughout the film.

Concrete Cowboy (2020)

Sent to live with his estranged father for the summer, a rebellious teen finds kinship in a tight-knit Philadelphia community of Black cowboys.

Hard things come before good things.

This mantra is repeated by many characters in this debut feature by Philadelphia-based director Ricky Staub.

A lot of hard things happen to Cole, the young man played by Stranger Things’ Caleb McLaughlin in an excellent, career trajectory-changing performance. He gets expelled from school. His mother drives him from Detroit to Philadelphia and leaves him with a father he barely knows. He gets caught up with the wrong crowd. He has unfortunate encounters with the police.

And that’s just the first twenty minutes.

The good things will come. They come to us all in due time. They come to Cole in the solace he finds in the horses present in this urban neighborhood, tended to by a community modeled after Philly’s real Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club.

It doesn’t feel like a traditional western at first. After all, westerns usually take place in the untamed frontier of the the Wild West. But here, the untamed frontier is Cole’s future. It’s uncertain, it’s prickly, it’s bleak. But Cole, thanks to the neighborhood and the guidance of his father played by a strong Idris Elba, is steered onto a path of respect, excellence, and responsibility — all traits commonly associated with your classic cowboy.

The film is quick to note that, despite media portrayals, 25% of those classic cowboys were black. And when you hear from some of the real life riders as the credits roll, you see that the tradition is still alive and well in North Philly.

Looking for even more options? Try:

Black Rodeo (1973) for a documentary about a rodeo that takes place, for the most part, in Harlem.

Blazing Saddles (1974) for the Mel Brooks sendup of the genre with a surprising amount of social commentary present throughout.

Hell on the Border (2019) for a modern day version of the classic western, detailing the true story of Bass Reeves, the first black marshal in the Wild West.

Credit: Each plot synopsis comes from Letterboxd via TMDb.