Easy Rider: Communion in the Wilderness

The New Hollywood classic is as much a film about community and acceptance as it is about independence and rebellion.

by Jeffrey Webb

A few minutes into Easy Rider, Peter Fonda tears off his wristwatch, tosses it down into the dirt. He revs up his motorcycle and hits the road. Steppenwolf’s “Born to Be Wild” blasts on the soundtrack. Opening credits roll.

Take a look at some other songs on the Easy Rider soundtrack: “I Wasn’t Born to Follow,” “If I was a Bird,” Hendrix’s “If 6 was 9.” This is a movie about freedom. Rebellion. It screams rebellion as loud as an engine’s roar.

And yet, despite its fiercely independent spirit, there are moments around dinner tables and campfires, quiet moments of communion and connection between strangers. Just as much as it is a movie about rebellion, Easy Rider is also a movie about brotherhood, fellowship, and acceptance.

Easy Rider rolled into theaters July 14, 1969, a week out from Neil Armstrong stepping foot on the moon. This was a time when New Hollywood was still new, a time when America was firmly entrenched in Vietnam and still reeling from the assassinations of JFK, RFK, MLK, Malcolm X. America was coming to terms with free love and women’s lib. Nixon was president, Cassius Clay was now Muhammad Ali, and the Manson murders wouldn’t happen for another month.

On the surface, Easy Rider is a good time. Put the movie on in the background of a party and you have a pretty good playlist of classic rock tunes. There’s beautiful scenery, humor, drugs, sex. On a deeper level, however, Easy Rider chronicles wasted youth. It mourns the failures and shortcomings of the counterculture movement in 1960s America. The film’s leads are stand-ins for the movement, chasing pleasure that burns out fast as a joint.

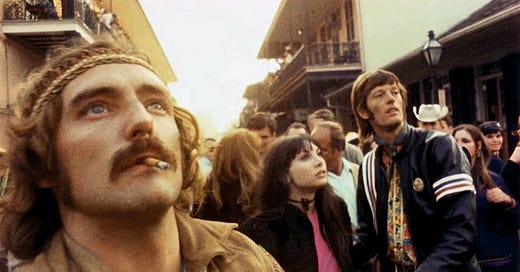

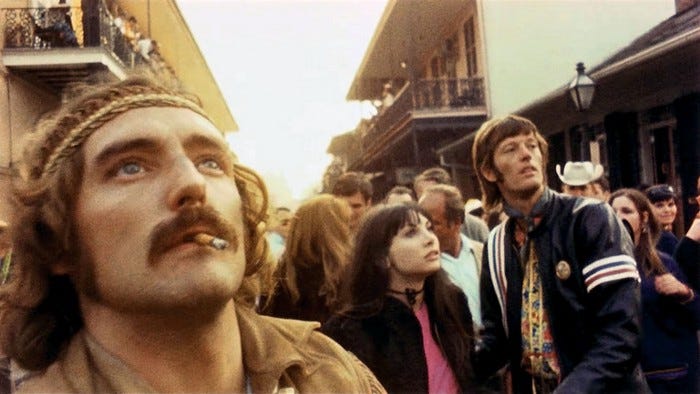

Wyatt and Billy (Fonda and Dennis Hopper, respectively) are cowboys here, outlaws, their motorcycles their steeds. They’ve made a drug deal out west, scored a bunch of cash. Looking to celebrate, they head east to Mardi Gras, taking in the landscape, cruising through Monument Valley not unlike characters in a John Ford film. At night, they bed down by a fire in the wilderness. “Out here in the wilderness, fighting Indians and cowboys on every side,” Billy says. We see America through their eyes.

Think of Wyatt as Christ, Billy as a sometimes misguided disciple. Think of them as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, only instead of windmills they’re chasing the American Dream. Wyatt and Billy navigate the highway frontier with a “live and let live” attitude. They meet resistance along the way. They are denied a room at a roadside inn, like the Holy Family a couple thousand years prior in Bethlehem. They are denied service at a southern lunch counter, not because of the color of their skin but because of the length of their hair.

The script is episodic. Hopper directs and shares screenwriting credit with Fonda and Terry Southern. The film’s first half meanders more so than the second half, Wyatt and Billy drifting from one episode to the next like a haze of smoke. Just as they are rejected by some, they are welcomed by others. They dine with a white farmer and his Mexican wife and children. The family prays before the meal. Wyatt, ever Christlike, admires them. He looks over the land, the dinner table, tells the farmer, “You sure got a nice spread here.” Later, Wyatt and Billy encounter a hitchhiker, a hippie who takes them back to his commune. Billy is skeptical, but Wyatt reassures his disciple. “Everything’s all right,” Wyatt says. At the commune, the traveling duo again partakes in a meal with strangers.

At one point the duo is arrested for riding their motorcycles through a small-town parade. Is this akin to Christ’s entrance to Jerusalem riding an ass? “Do you know who this is, man?” Billy asks the arresting officers, gesturing to Wyatt. Meanwhile, a sign hangs on the jail wall: “Jesus Christ — the same yesterday, today, and forever.”

In jail, they meet George, a drunken lawyer played by Jack Nicholson. A young Nicholson, every bit as charismatic here as he is in any of his later roles.

The movie reaches its apex of freedom with George riding on the back of Wyatt’s motorcycle, football helmet strapped on his head, arms outstretched like a bird flying. George is best described as a square. He lives with his mother. He insists upon calling grass “marijuana” and smokes for the first time only after he has met Wyatt and Billy. “It gives you a whole new way of looking at the day,” Wyatt tells George in regard to marijuana. “I sure could use that,” George replies. With Wyatt and Billy, George finds an acceptance and independence he otherwise lacks.

The innocence of the film’s first half is juxtaposed with disillusionment and loss in the second half. Wyatt’s anguish on a bad trip of acid echoes the agony of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. By the end credits, there’s been more than one case of violence.

Billy: “Out here in the wilderness, fighting Indians and cowboys on every side.”

George: “This used to be a hell of a country.”

The movie poster tagline says it all: “A man went looking for America and couldn’t find it anywhere.”

The Gospel of John doesn’t end with Christ’s ascension to Heaven. It ends with a somber moment of fellowship among Christ and his disciples. Christ, risen from the dead, tends a fire and invites his disciples to the shoreline to share in a meal of bread and fish. Communion. It is a reflective, quiet ending to a book full of blood and miracles.

“We blew it,” Wyatt meditates in Easy Rider’s penultimate scene. “We blew it, man.”

Ultimately, Wyatt and Billy are both too apolitical, too hedonistic, to be anybody’s messiahs. They are flawed. They are, however, only human. By riding along with them vicariously through the power of cinema, we are reminded of what it is to be human. It reminds us we are all invited to the fire burning in the early morning light, whether it be Christ on the beach beckoning his disciples or Wyatt and Billy out there in America’s wilderness, sharing a joint, offering us a hit.